Name: Noura Alyouha

Location: Québec, Canada

Child’s Birth Year: 2021

Keywords: Prematurity, Twins, Work in Medical Field

Noura, originally from Kuwait, and her husband, originally from the UK, moved to Montreal for Noura’s residency. Noura is a physician who finished her ENT training and is currently doing a fellowship in head and neck oncology surgery. While Noura was used to assuming the role of the provider, never did she think she would so intimately experience what it felt like to be on the other side—to be a patient and a family member forced to cope with serious illness. But then came the birth of her two boy twins, Ferris and Zane, who were born premature at twenty-nine weeks in January 2021. While Ferris experienced the HIE event, both twins were in critical condition due to complications related to prematurity.

Noura’s pregnancy was high risk to begin with, since she was having mono/di twins, meaning twins that share the same placenta. In the weeks before Ferris and Zane were born, Noura was heavily monitored, going in for an ultrasound every one to two weeks. Around December, Noura was put on bedrest because her cervical length was short, and she worried the whole time about premature birth. Never once did she consider HIE to be a concern. About two days before the twins were born, Noura experienced severe back pains, and thought they might be a weird form of contractions. She also noticed decreased fetal movement and could really only feel one baby moving.

The next day, when she went to the hospital to get checked out, she found all her worries were coming to life—she was in preterm labor. The physicians found a good heart rate on both twins, so the fetal movement became less of a concern. Instead, the main focus was on trying to stop the labor so the twins would be able to develop in utero for longer. Noura was put on IV magnesium, which seemed to control the contractions. Because she wasn’t in active labor, Noura was moved the next day from the main birthing center to the general ward, still on intermittent fetal monitoring.

While she was in the general ward, the doctors noticed there wasn’t the expected variability in Ferris’s heart rate. To be safe, the doctors moved Noura back closer to the delivery area so they could do continuous monitoring. That night, Noura’s back pains came back in full force, and she was physically and mentally drained from being awake for over a day straight. She told the overnight OB that she needed better pain management and that they needed to either make the decision to deliver the babies or not. Sitting in this terribly uncomfortable state of limbo for so long wasn’t a feasible option. The OB told her that the recent ultrasound was reassuring—Ferris did have decelerations in his heart rate, but it always rebounded.

Finally, Noura was disconnected from the fetal tracing for a few hours so she could get much-needed rest in a bed on the general ward. A few hours later, though, Noura’s attempts at sleep were interrupted by feelings of extreme nausea and the sensation of her water breaking. She immediately called the nurse, and when she was again hooked up to the fetal tracing, this time both babies were experiencing frequent heart decelerations. While Noura was receiving a swab test to see if her water had actually broken or not, one of the twin’s heart beats was lost completely, so she was quickly rushed into the OR for an emergency C-section.

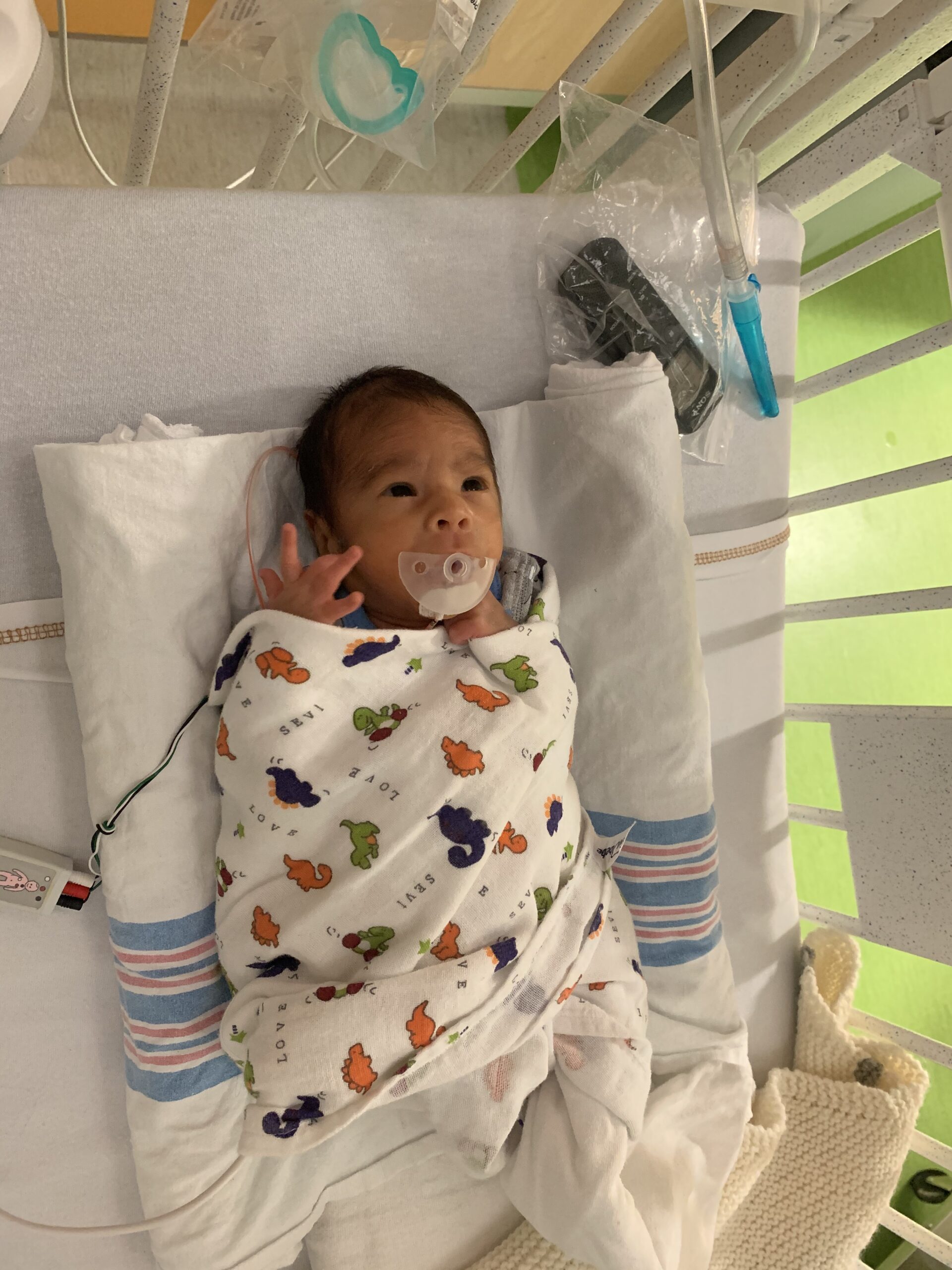

The babies were born sick, unresponsive, and needed to be intubated. They were rushed to the NICU and received EEG monitoring to check for seizures. Zane didn’t have any seizures, but Ferris had many seizures that first night, so he was put on heavily sedating, anticonvulsant medications. In the days after their birth, Ferris showed signs of potential brain damage, and physicians suspected he might have suffered an HIE event in utero. However, because he was born so early, it was extremely difficult to discern if symptoms were associated with HIE or just due to prematurity, and very little is known about MRIs in premature babies. It would be virtually impossible to make any real conclusions solely based on an MRI for Ferris, but one doctor had the idea of also doing an MRI on Zane to be used for comparison. Ferris went off to get his MRI first, but Zane’s MRI had to be cancelled because he had a bowel perforation right before his scheduled test.

The radiologists consulted professionals from various other health centers to help interpret Ferris’s MRI as best as possible. At the family meeting to discuss the results, a palliative care team was brought in. The neurologist told Noura and her husband that the damage to Ferris’s brain was more severe and global than initially anticipated, that the brain stem and deeper structures in the brain were essentially wiped out, and that an HIE event had most likely occurred a few days before the actual delivery. The team of providers went on to explain that, based on these results, Ferris probably would never do much of anything. They would be surprised if he’d ever be able to eat, talk, walk, or even breathe on his own. Noura felt like she was being flooded with this definitively grim picture, and she was pushed in that meeting to decide about whether to withdraw life-sustaining treatment. She had literally just given birth and barely had time to process any information, so she said she needed more time.

What the neonatologist said next is something she will never forget: “I just want you to know that it will be easier now. The longer you wait, the harder it will be to make the decision. In the future, Ferris might be extubated, so it won’t be as easy to pull the plug.”

Noura understood the neonatologist’s argument—the sicker Ferris was, the faster he would die if they chose to withdraw life support. But, still, in Noura’s mind, nothing could ease the pain of potentially losing a baby she had been bonding with for the past seven months. Noura advises medical professionals to be careful with the words they use to describe a situation, especially when that situation is a matter of life and death. She would also tell them to avoid ascribing their personal opinions about the value of a life with disability on the families they interact with and, instead, deliver the facts. Through the Hope for HIE group, Noura sees how many parents have children with disabilities, yet still love them dearly and still lead good lives. Thus, assuming that no parent would take on the “burden” of having a child with a disability is both unwarranted and untrue.

Moreover, as a physician herself, Noura understands that the job of the physician is to be as up front and realistic as possible. After she was painted that grim picture of the worst-case scenario, Noura would have appreciated it if she’d been referred to parent support resources, such as Hope for HIE, to visualize the different possible outcomes. Just telling families “We don’t know what is going to happen, but it could be pretty bad,” gives nothing for families to work off of. However, admitting to that uncertainty, while simultaneously directing parents to families who might be further along in the HIE journey, helps new parents put all the grayness into perspective. It was only after finding Hope for HIE on her own and seeing how various families were coping with taking care of children with diverse outcomes that Noura was able to see what the physicians meant by the “wide range of outcomes.”

Ultimately, Noura was confident with her choice to withhold making a final decision right away. When doctors were making bold claims about Ferris’s lack of abilities, Noura remained skeptical about how certain Ferris’s prognosis was made to seem. At the time of the MRI, and all the various neurological assessments, Ferris was on many heavily sedating medications. If an adult was on all these medications, doctors wouldn’t be able to appropriately assess neurological response, so how were they able to properly assess a premature baby? In order to make the heavy decision, Noura consulted many of her medical colleagues and sought the advice of as many professionals as possible given the complexity of the situation. Noura’s neurosurgeon brother-in-law confirmed her thoughts that the MRI couldn’t clearly determine what Ferris would be able to do down the line, especially if the concept of neuroplasticity was considered.

Before a final consensus was reached, Ferris essentially made the decision for Noura through the improvements he began to make. He came off all cardiac medications, and his cardiac echo was fine. He started urinating and having regular bowel movements. Once he was extubated, he was breathing normally, on his own, and even feeding from bottles. In fact, Ferris made so much progress that he was discharged from the NICU at seven weeks old, a few weeks before his twin brother Zane came home.

Now, Ferris is doing better than anyone could have envisioned. He continues to drink milk and gain weight at a steady pace, he has decent head control, and Keppra has been effectively controlling his seizures. Ferris is young, so there’s a lot of uncertainty about the future, but Noura tries her best to take it day by day.

Throughout this entire journey, Noura is grateful for all the support she has received. In the NICU, even though Noura and her husband never made the decision to withdraw care, the palliative care worker continued to check in to see how they were doing. She appreciated how there were many multidisciplinary team members involved in the NICU, such as a spiritual advisor and social worker. Even though she never went to therapy, Noura was glad the option of counseling services was offered to her. Because there is so much trauma and guilt concomitant with being an HIE parent, Noura hopes that, in the future, psychological evaluations facilitated by a counselor will become a standard practice during a NICU stay.

Noura experienced immense guilt after the birth of the twins, thinking, if only she hadn’t pushed the doctors to either deliver the twins or take her off monitoring. Even though she knows there is no singular person who is at fault, it’s hard not to feel like a failure as a mother, and as a physician, who couldn’t prevent the suffering of her own children. When Noura finds herself spiraling down this rabbit hole of self-blame, she reminds herself that, in life, bad things sometimes just happen, and all she can do is learn to roll with the punches. She is also unbelievably grateful for Hope for HIE, as reading the advice of other parents has been her number one resource to find information. Even though she sometimes feels out of place, since her experience with prematurity and twins is so niche, she has been able to find bits and pieces of her journey in the journeys of other community members.

The fact that Noura is a physician herself has been both a blessing and a curse. Because she is an ENT, she was able to worry less about certain things. For instance, when Ferris didn’t pass the hearing test the first time, she didn’t panic that this meant he’d never be able to hear. She knew that many babies don’t pass the first time around. Just as she predicted, Ferris ended up passing his second attempt at the hearing test. On the other hand, because she does have so much medical knowledge, Noura often finds herself informally screening the twins for signs of more serious issues, while her husband is able to relax a bit more and just have fun with the boys. When the twins are fussy about drinking milk, Noura’s thoughts first jump to, “What if they are dehydrated?” Her husband, on the other hand, can brush it off, reminding her that infants are just sometimes whiny. In the moments where Noura finds herself waiting for the other shoe to drop, she is grateful for her husband’s ability to reassure her and pull her back to the present moment.

It’s not easy to stop worrying about everything that could potentially go wrong in the future, but Noura holds on to the advice that the physiotherapist and occupational therapist gave to her before Ferris left the NICU: “Noura, Ferris is here now, and he has already made so much progress. Let’s stop concentrating on how awful the future might be, and instead start shifting to giving Ferris as much goodness as possible. Let’s help him become his best self.” This message is one Noura sees reiterated in the Hope for HIE community, and it has really hit home to hear it coming from parents who are also going through the process. Ferris doesn’t need a 24/7 physician incessantly analyzing him for signs of illness. What he needs most is a mother who will empower him to reach his full potential and love him regardless of what that potential may look like.

To be the best mother and caretaker for Ferris and Zane, Noura realizes how important it is to take care of herself as well. In the first few weeks, Noura and her husband didn’t look after their own well-being as much as they now wish they had. Especially having, not only one, but two, new babies with such uncertain long-term outcomes, Noura found herself losing sight of who she was as an individual. She was exhausted at the end of every day, and the life she had always known, with the activities she used to enjoy, slipped away.

However, once everything was more settled, she eventually went back to work, while her husband stayed home with the twins. Being able to go back to work and be in the operating room (this time as the physician, instead of the patient) was healing for Noura, as it’s truly her calling. While she’s at work, she has time to herself, when she isn’t constantly wondering if that movement Ferris made was an indication of infantile spasms. And she has discovered that she is now able to be more engaged with the boys when she’s at home, since she’s no longer so mentally drained. All in all, Noura would emphasize to other HIE parents that, while it is hard in the moment to think self-care is a priority, it truly is essential. Becoming a parent to a child with HIE will drastically change one’s life, but that doesn’t mean it needs to completely wipe away everything about the life that already existed. No matter happens down the road, Noura has hope that her family will get through it. She feels fortunate to have the support resources—both financial and social—to accommodate any kind of outcome. Her extended family is amazing at helping out with childcare, and she is blessed that, because she lives in Canada, where healthcare is socialized, she doesn’t have to worry about the costs of follow-up care. She fully acknowledges that it is certainly easier to be optimistic when you have the privileges she does, but she hopes that the parents who need to pay out-of-pocket, or may not live close to relatives, can still find other vehicles of support, perhaps through connecting with the wonderful people in the HIE community. Noura chooses to be open about her story to also serve as that vehicle of support, especially for parents dealing with the largely unexplored, undefined intersectionality of HIE and prematurity.

Connect with families, read inspiring stories, and get helpful resources delivered right to your inbox.